V

|  |  |  |

To reach its classic phase the Gothic style needed no more than a hundred years—from Suger’s St.-Denis to Pierre de Montereau’s; and we should expect to see this rapid and uniquely concentrated development proceed with unparalleled consistency and directness. Such, however, is not the case. Consistent the development is, but it is not direct. On the contrary, when observing the evolution from the beginning to the “final solutions,” we receive the impression that it went on almost after the fashion of a “jumping procession,” taking two steps forward and then one backward, as though the builders were deliberately placing obstacles in their own way. And this can be observed not only under such adverse financial or geographical conditions as normally produce a retrogression by default, so to speak, but in monuments of the very first rank.

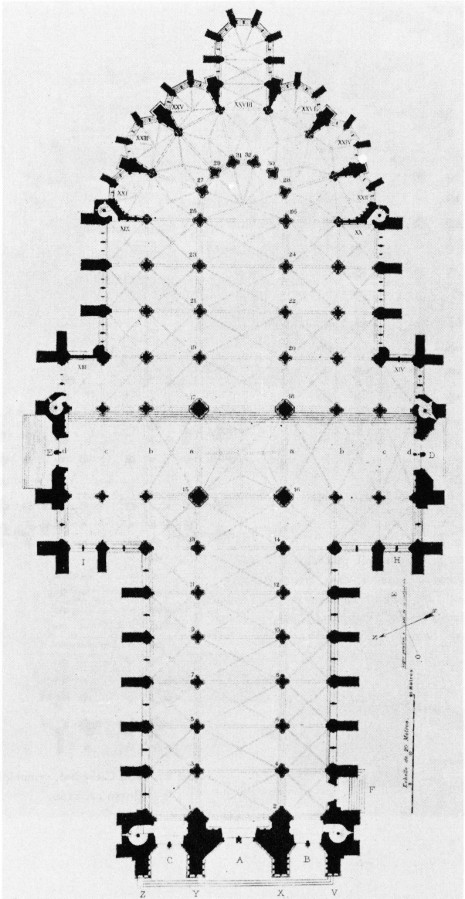

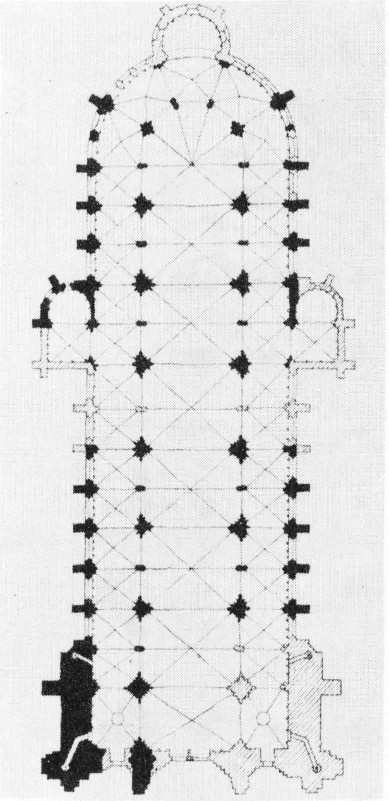

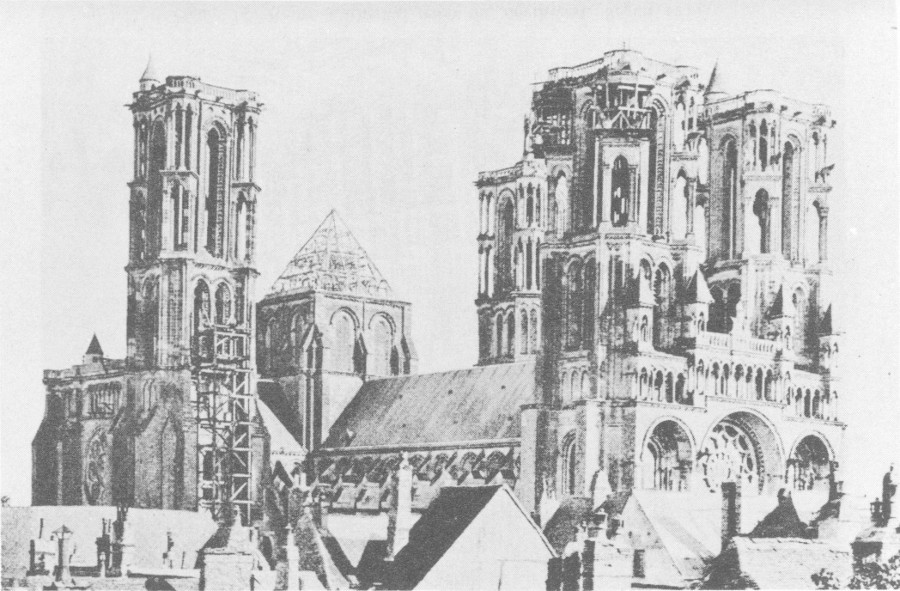

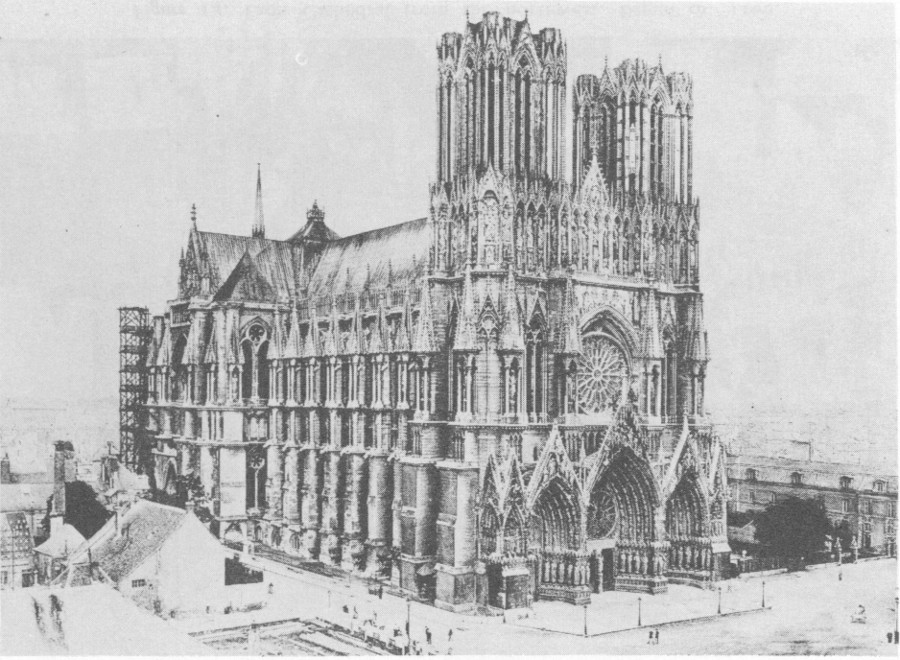

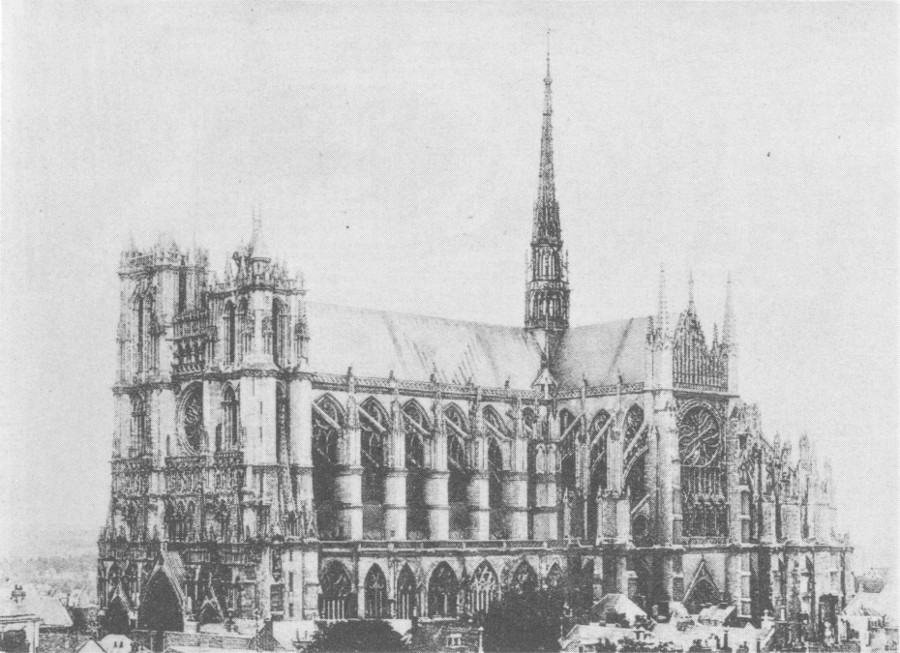

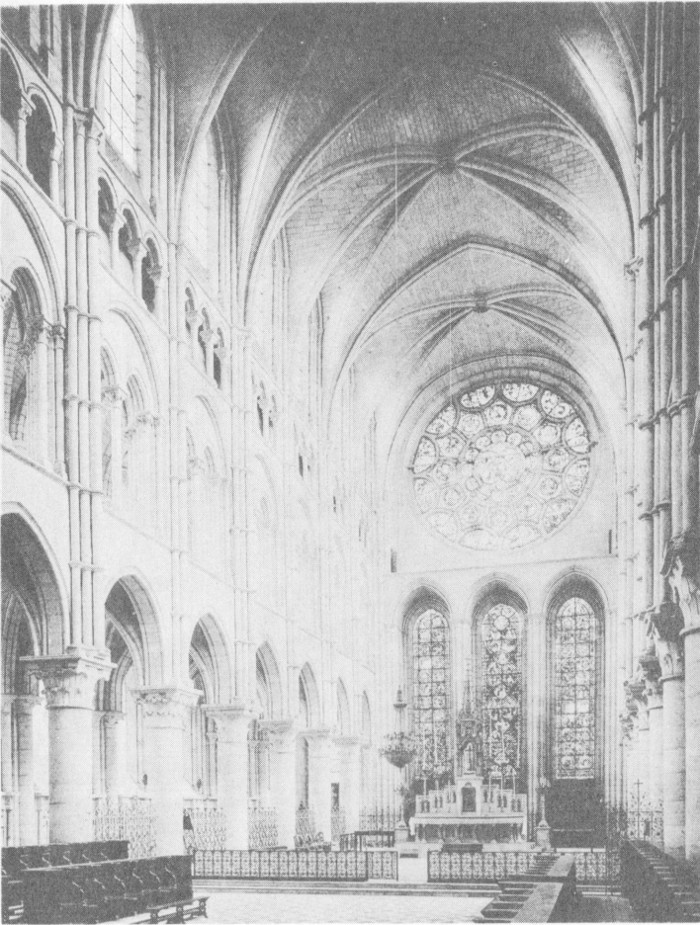

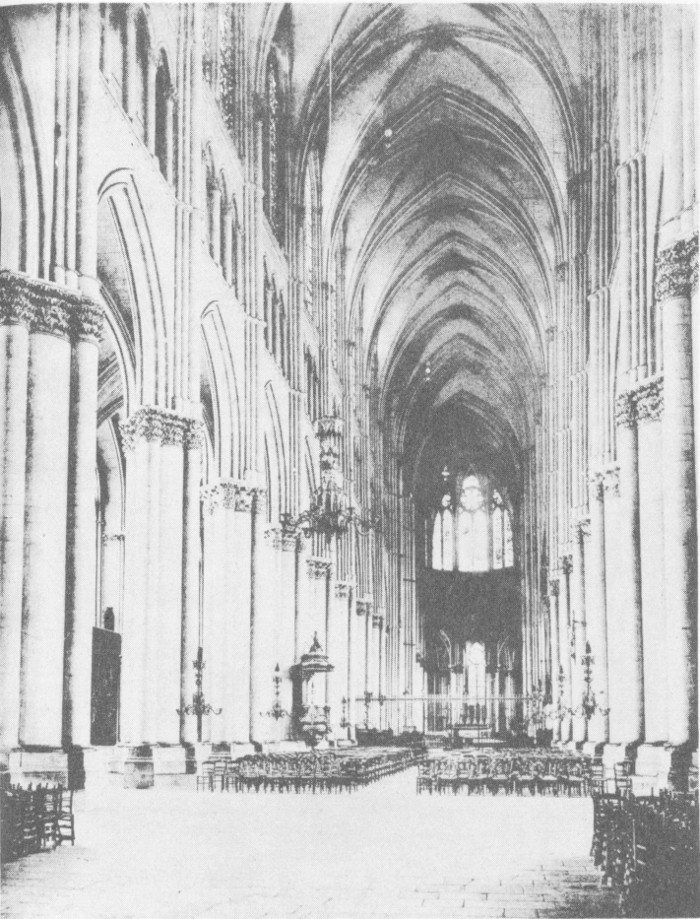

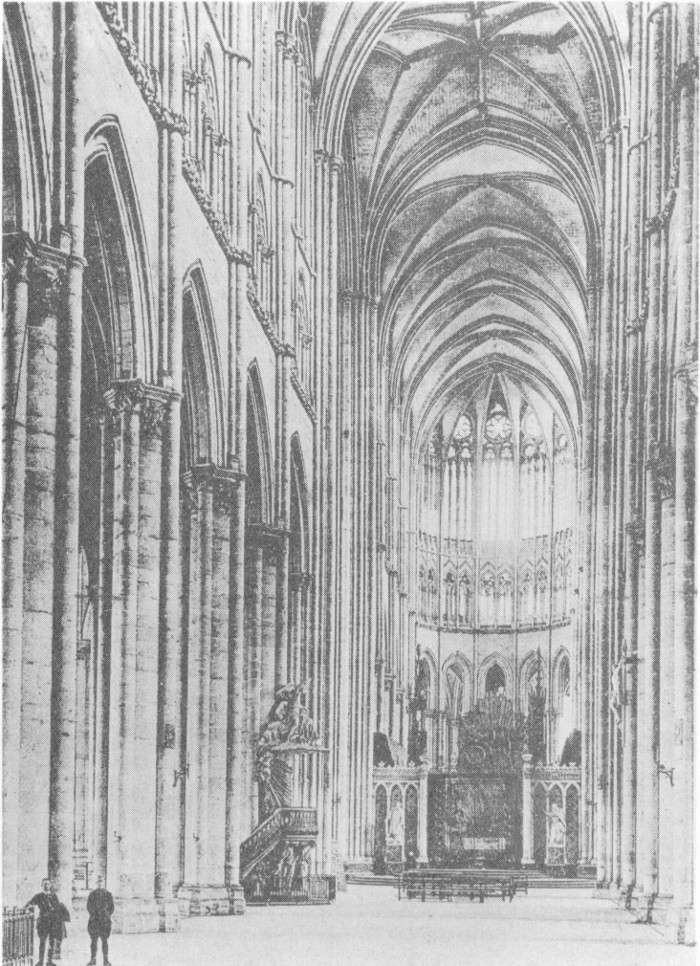

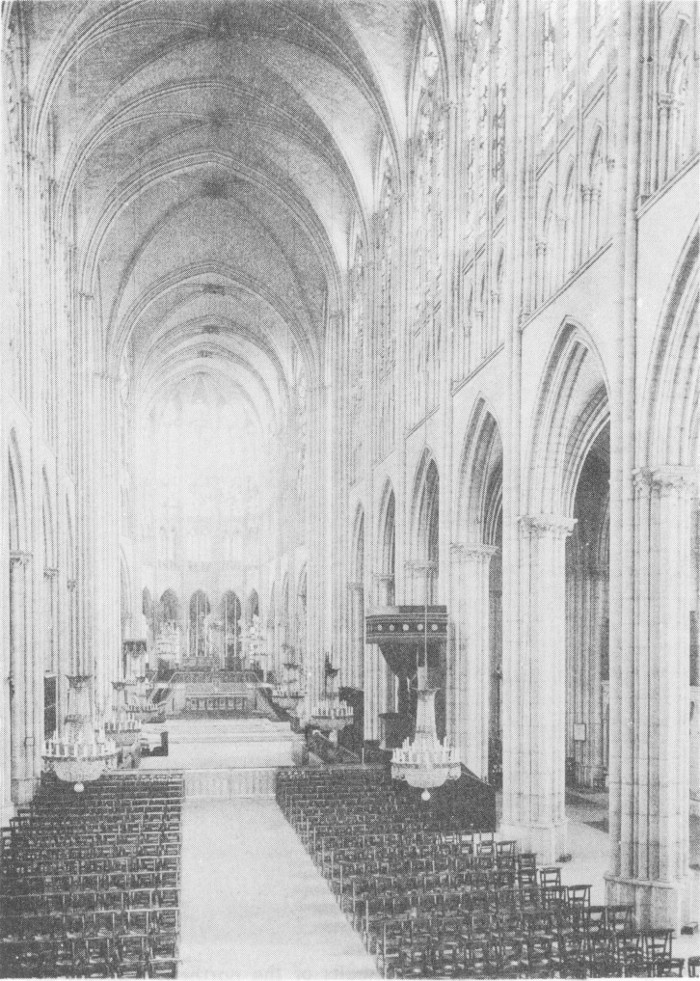

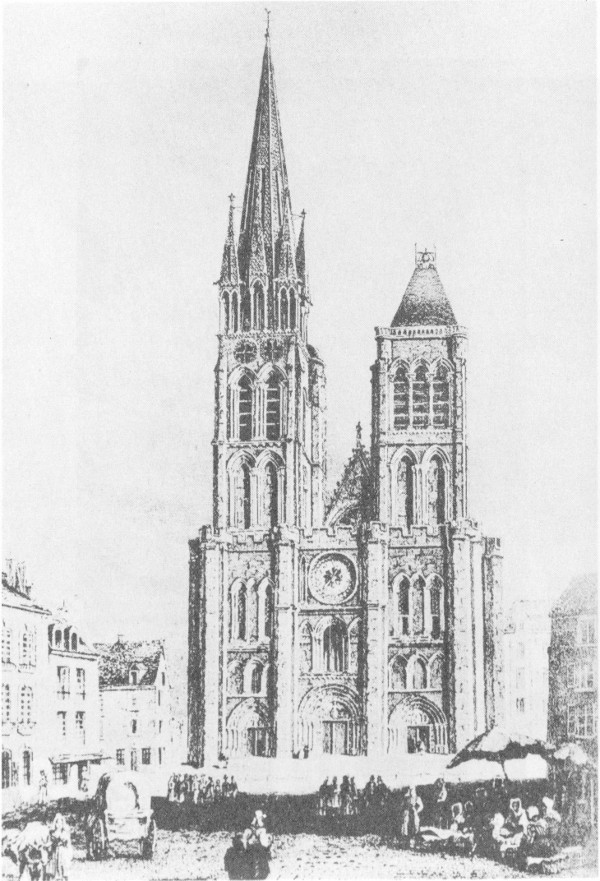

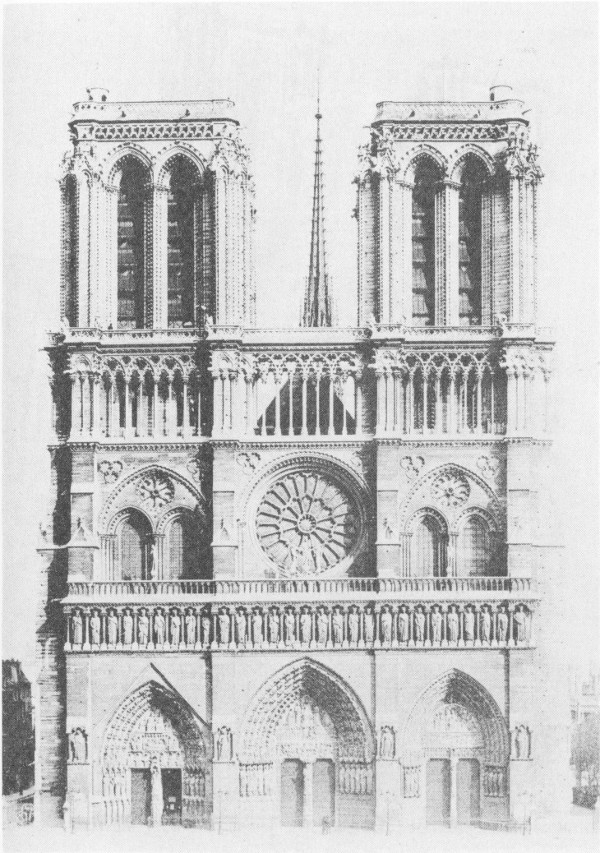

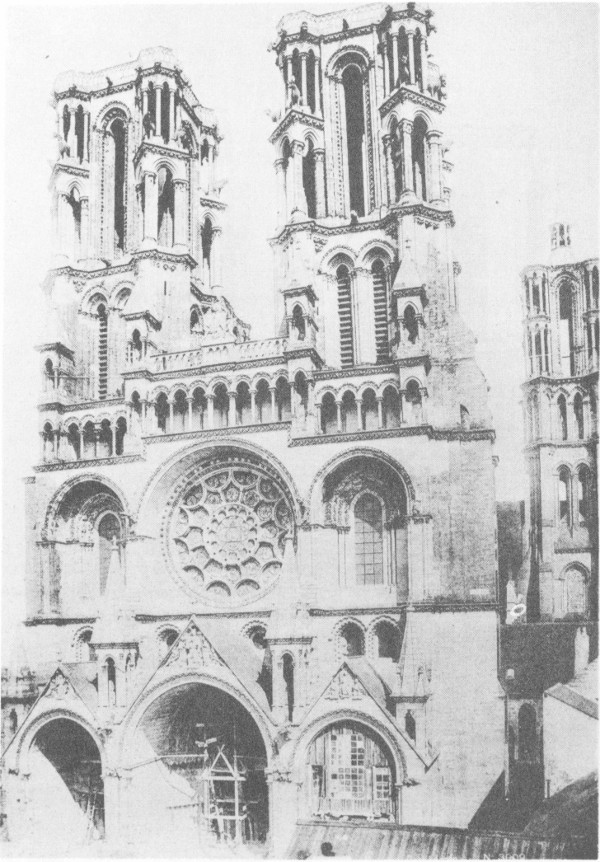

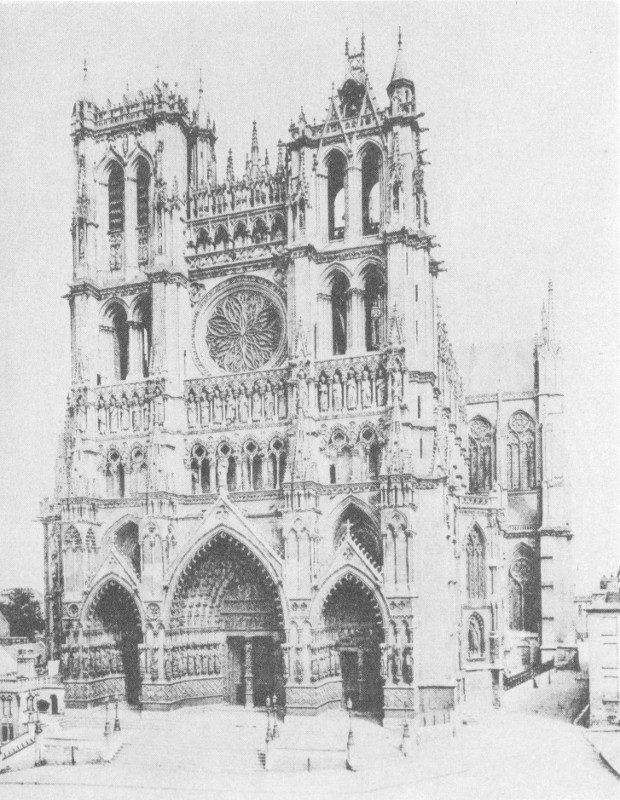

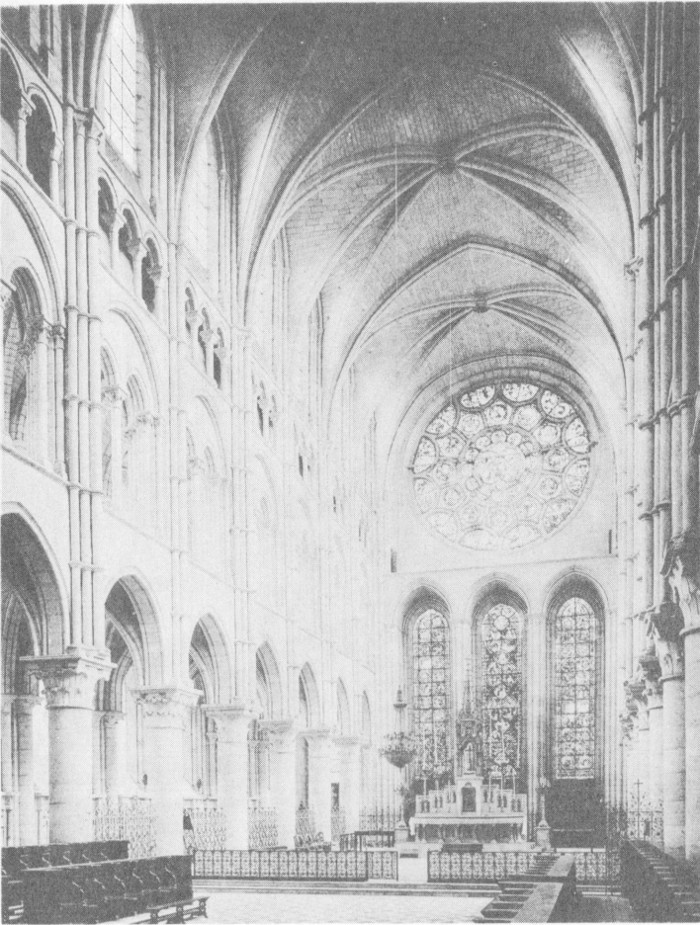

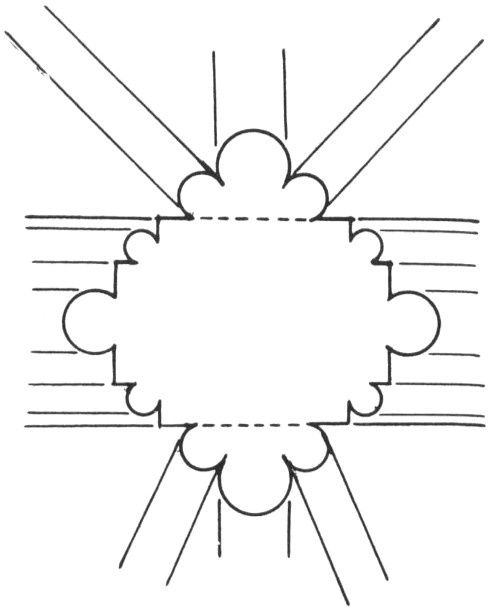

The “final” solution of the general plan was reached, we remember, in a basilica having a tripartite nave; a transept, likewise tripartite and distinctly projecting from the nave but merging, as it were, into the quinquepartite fore-choir; a concentric chevet with ambulatory and radiating chapels; and only two towers in front (fig. 11 and 16). At first glance, the natural thing would have been a rectilinear development starting from St.-Germer and St.-Lucien-de-Beauvais which anticipate nearly all these features in the early twelfth century. Instead, we find a dramatic struggle between two contrasting solutions each of which seems to lead away from the ultimate result. Suger’s St.-Denis and Sens Cathedral (fig. 12) provided a strictly longitudinal model, with only two towers in front and the transept either stunted or entirely omitted—a plan adopted in Notre-Dame of Paris and Mantes, and still retained in the High Gothic Cathedral of Bourges. Note 45 As though in protest against this, the masters of Laon (fig. 13 and 14)—possibly swayed by the unique location of their cathedral on the crest of a hill—reverted to the Germanic idea of a multinomial group with a projecting, tripartite transept and many towers (as exemplified by the Cathedral of Tournai), and it took the succeeding generations two more cathedrals to get rid of the extra towers surmounting the transept and the crossing. Chartres was planned with no less than nine towers; Reims, like Laon itself, with seven (fig. 15); and it was not until Amiens (fig. 16) that the disposition with only two front towers was reinstated.

|  |  |  |

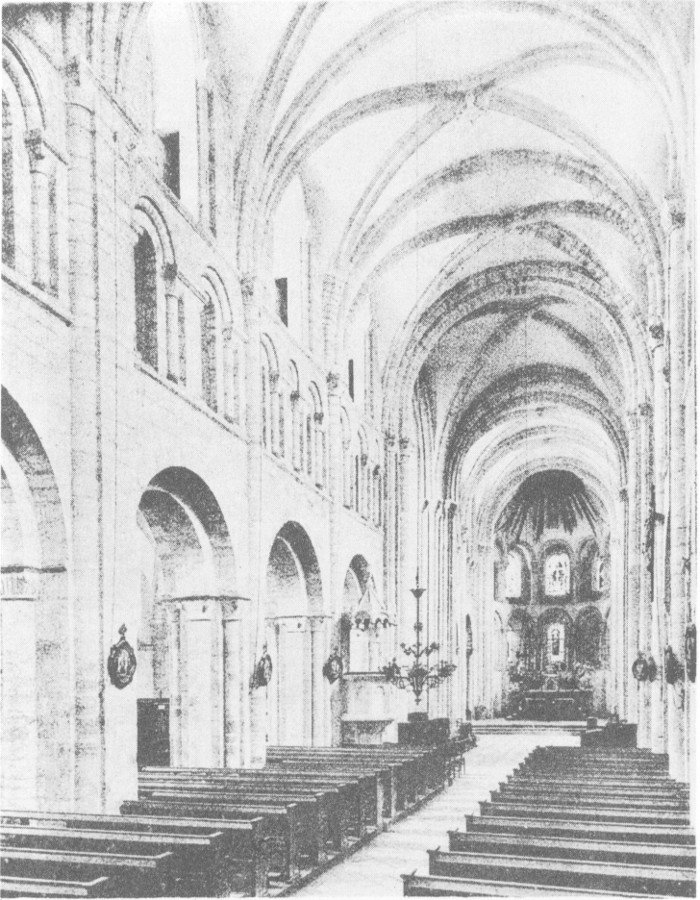

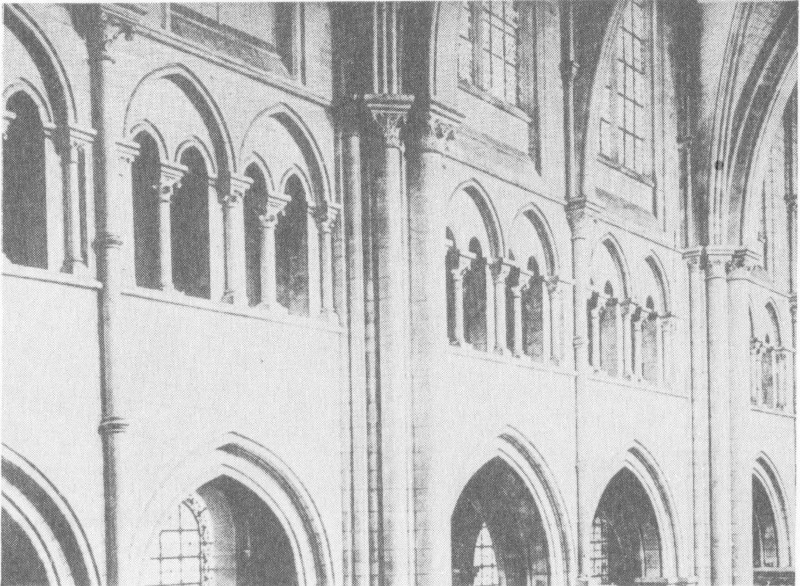

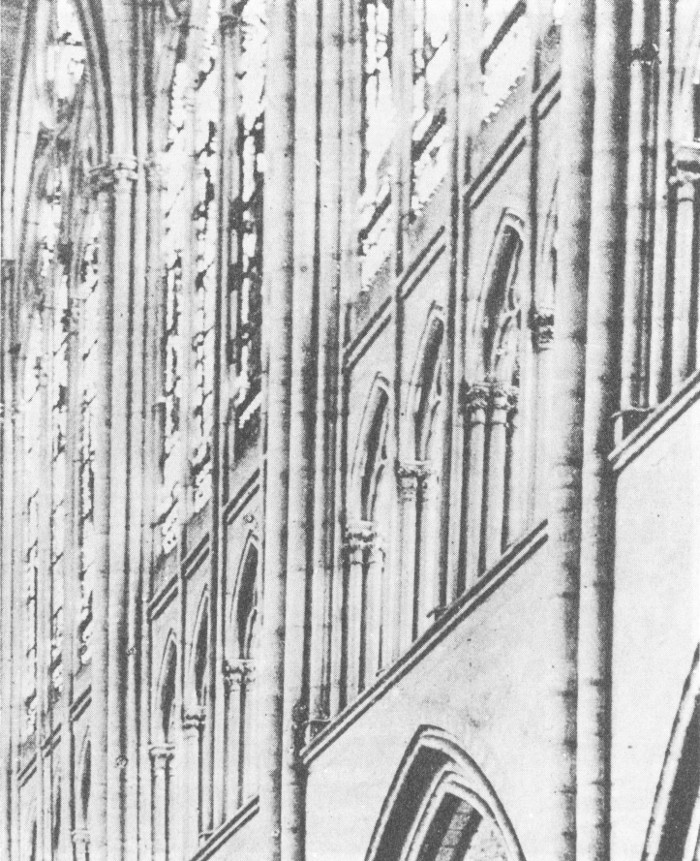

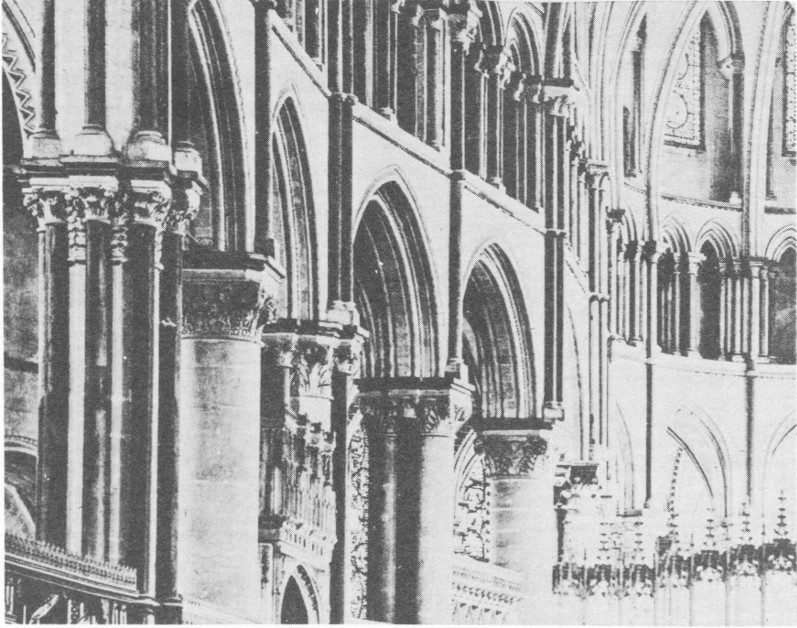

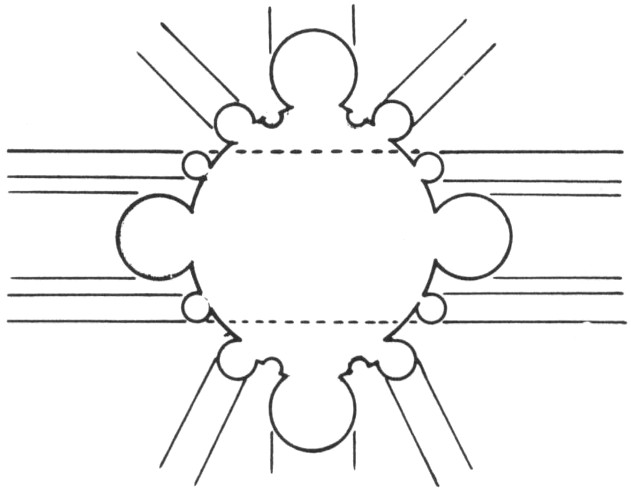

Similarly, the “final” solution of the nave composition (fig. 19-22) implied, in plan, a succession of uniform, oblong, quadrupartite vaults and uniform, articulated piers; and, in elevation, a triadic sequence of arcades, triforium, and clerestory. Again it would seem that this solution might have been reached by going ahead, straightforwardly, from such early twelfth-century prototypes as St.-Etienne-de-Beauvais or Lessay in Normandy (fig. 17). Instead, all major structures prior to Soissons and Chartres sport sixpartite vaults over monocylindrical piers (fig. 18) or even revert to the antiquated “alternating system.” Their elevation shows galleries which, in the most important buildings later than Noyon, are combined with a triforium (or, as in Notre-Dame- de-Paris, with the equivalent thereof) into a four-story arrangement (fig. 18). Note 46

|  |  |  |

In retrospect, it is easy to see that what seems to be an arbitrary deviation from the direct road is in reality an indispensable prerequisite of the “final” solution. Had it not been for the adoption of the many-towered group in Laon, no balance would have been achieved between the longitudinal and the centralizing tendencies, much less a unification of a fully developed chevet with an equally fully developed tripartite transept. Had it not been for the adoption of sixpartite vaults and a four-story elevation, it would not have been possible to reconcile the ideal of a uniform progression from west to east with the ideals of transparency and verticalism. In both cases the “final” solutions were arrived at by the ACCEPTANCE AND ULTIMATE RECONCILIATION OF CONTRADICTORY POSSIBILITIES. Note 47 Here we come upon the second controlling principle of Scholasticism. And if the first —manifestatio—helped us to understand how Classic High Gothic looks, this second—concordantia—may help us to understand how classic High Gothic came about.

All that mediaeval man could know about divine revelation, and much of what he held to be true in other respects, was transmitted by the authorities (auctoritates): primarily, by the canonical books of the Bible which furnished arguments “intrinsic and irrefutable” (proprie et ex necessitate); secondarily, by the teachings of the Fathers of the Church, which furnished arguments “intrinsic” though merely “probable,” and of the “philosophers” which furnished arguments “not intrinsic” (extranea) and merely probable for this very reason. Note 48 Now, it could not escape notice that these authorities, even passages of Scripture itself, often conflicted with one another. There was no other way out than to accept them just the same and to interpret and reinterpret them over and over again until they could be reconciled. This had been done by theologians from the earliest days. But the problem was not posed as a matter of principle until Abelard wrote his famous Sic et Non, wherein he showed the authorities, including Scripture, disagreeing on 158 important points—from the initial problem whether or not faith ought to seek support in human reason down to such special questions as the permissibility of suicide (155) or concubinage (124). Such a systematic collection and confrontation of conflicting authorities had long been a practice of the canonists; but law, though God-given, was, after all, man-made. Abelard showed himself very conscious of his boldness in exposing the “differences or even contradictions” (ab invicem diversa, verum etiam invicem adversa) within the very sources of revelation when he wrote that this “would stimulate the reader all the more vigorously to inquire into the truth the more the authority of Scripture is extolled.” Note 49

After having laid down, in his splendid introduction, the basic principles of textual criticism (including the possibility of clerical error in even a Gospel, such as the ascription of a prophesy of Zacharias to Jeremias in Matthew, XXVII, 9), Abelard mischievously refrained from proposing solutions. But it was inevitable that such solutions should be worked out, and this procedure became a more and more important part, perhaps the most important part, of the Scholastic method. Roger Bacon, shrewdly observing the diverse origins of this Scholastic method, reduced it to three components: “division into many parts as do the dialecticians; rhythmical consonances as do the grammarians; and forced harmonizations (concordiae violentes) as used by the jurists.” Note 50

It was this technique of reconciling the seemingly irreconcilable, perfected into a fine art through the assimilation of Aristotelian logic, that determined the form of academic instruction, the ritual of the public disputationes de quolibet already mentioned, and, above all, the process of argumentation in the Scholastic writings themselves. Every topic (e.g., the content of every articulus in the Summa Theologiae) had to be formulated as a quaestio the discussion of which begins with the alignment of one set of authorities (videtur quod . . .) against the other (sed contra . . .), proceeds to the solution (respondeo dicendum . . .), and is followed by an individual critique of the arguments rejected (ad primum, ad secundum, etc.)—rejected, that is, only insofar as the interpretation, not the validity, of the authorities is concerned.

Needless to say, this principle was bound to form a mental habit no less decisive and all-embracing than that of unconditional clarification. Combative though they were in dealing with each other, the Scholastics of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were unanimous in accepting the authorities and prided themselves on their skill in understanding and exploiting them rather than on the originality of their own thought. One feels the breath of a new era when William of Ockham, whose nominalism was to cut the ties between reason and faith and who could say: “What Aristotle thought about this, I don’t care,” Note 51 goes out of his way to deny the influence of his most important forerunner, Peter Aureolus. Note 52

An attitude similar to that of High Scholasticism must be presupposed in the builders of the High Gothic cathedrals. For these architects the great structures of the past had an auctoritas quite similar to that which the Fathers had for the schoolmen. Of two apparently contradictory motifs, both of them sanctioned by authority, one could not simply be rejected in favor of the other. They had to be worked through to the limit and they had to be reconciled in the end; much as a saying of St. Augustine had ultimately to be reconciled with one of St. Ambrose. And this, I believe, accounts to some extent for the apparently erratic yet stubbornly consistent evolution of Early and High Gothic architecture; it, too, proceeded according to the scheme: videtur quod—sed contra—respondeo dicendum.

I should like to illustrate this, most cursorily, by three characteristic Gothic “problems”—or, as we might say, quaestiones: the rose window in the west façade, the organization of the wall beneath the clerestory, and the conformation of the nave piers.

|  |  |  |

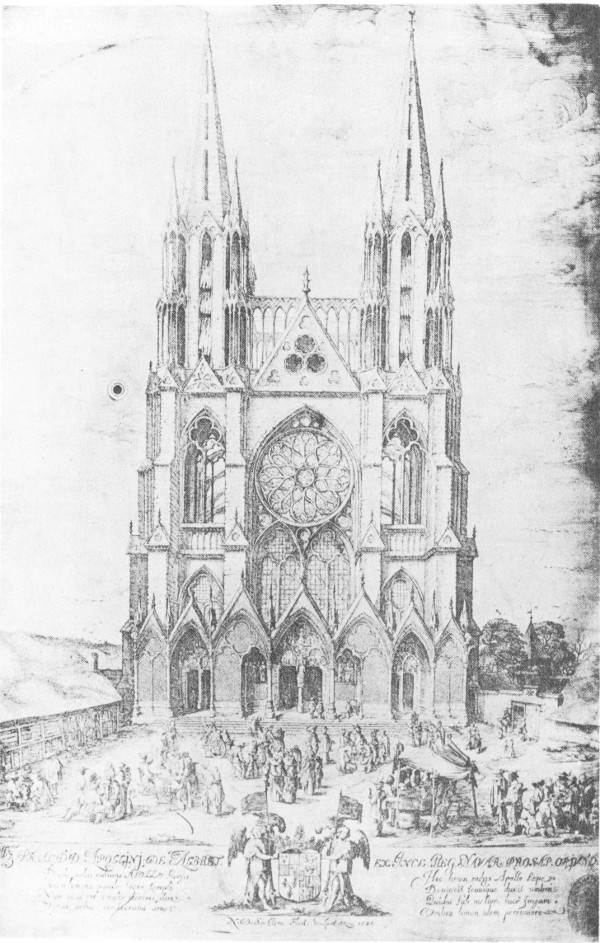

So far as we know, west façades were pierced by normal windows, and not by roses, until Suger—perhaps impressed by the magnificent specimen in the north transept of St.- Etienne in Beauvais—chose to adopt the motif for the west façade of St.-Denis, superimposing a magnificent Non upon the Sic of the big window beneath it (fig. 30). The further development of this innovation was fraught with great difficulties. Note 53 If the diameter of the rose remained comparatively small or was even reduced (as in Senlis), an awkward and “un-Gothic” space of wall was left on either side as well as underneath. If the rose was enlarged to approximately the full width of the nave, it tended to conflict with the nave vaults when seen from within and required on the exterior as wide an interval as possible between the buttresses of the façade, thus uncomfortably diminishing the space available for side portals. Apart from this, the very concept of an isolated, circular unit conflicted with the ideals of Gothic taste in general, and with the ideal of a Gothic façade—adequate representation of the interior—in particular.

Small wonder that Normandy and—with a very few exceptions—England plainly rejected the whole idea and simply enlarged the traditional window until it filled the available space (while Italy, characteristically, greeted the rose with enthusiasm because of its au fond anti-Gothic character). Note 54 The architects of the Royal Domain and Champagne, however, felt bound to accept a motif sanctioned by the authority of St.-Denis, and it is almost amusing to observe their perplexities.

The architect of Notre-Dame (fig. 31) was lucky in that he had a quinquepartite nave. Courageously though not quite honestly ignoring this fact, he built a tripartite façade the lateral sections of which were so wide in comparison to the middle that all problems were easily solved. The master of Mantes, however, had to make the distance between the buttresses considerably smaller than the width of the nave (as small, in fact, as was technically possible); and even then the space for the side portals was far from ample. The master of Laon, who wanted both a full-sized rose and generous side portals, resorted to a trick; he broke the buttresses so that their lower sections, framing the central portal, are closer together than the upper ones that frame the rose; and then he concealed the break by the enormous fig-leaf of his porch (fig. 32). The masters of Amiens, finally, with their inordinately slender nave, needed two galleries (one with kings, the other without) to fill the space between the rose and the portals (fig. 33).

|  |  |

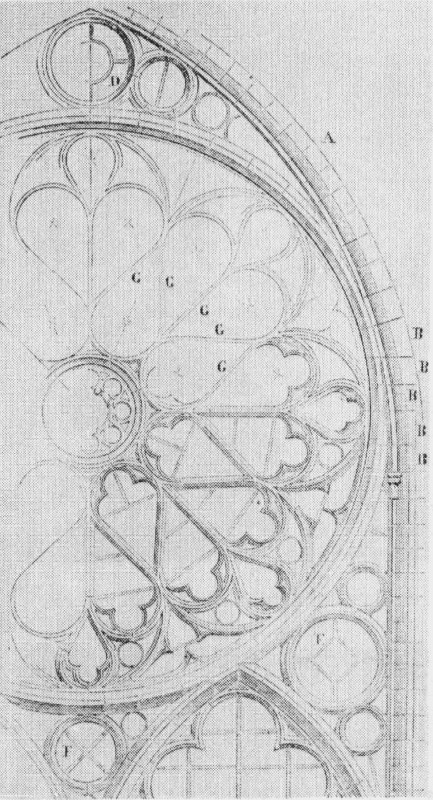

It was not until 1240-50 that the school of Reims, culminating in St.-Nicaise, discovered the “final” solution (fig. 34 and 35): the rose was inscribed within the pointed arch of a huge window, thereby becoming elastic, as it were. It could be lowered so as not to conflict with the vaults; the space beneath it could be filled with mullions and glass. The whole arrangement mirrored the cross section of the nave, and yet the window remained a window and the rose a rose. For the window-and-rose combination of St.-Nicaise is not, as might be thought, a simple enlargement of a bipartite bar- tracery window as seen, for the first time, in Reims Cathedral (fig. 36). In such a window the circular element surmounting the openings is not, as is the rose, a centrifugal but a centripetal form: not a wheel, with spokes radiating from a hub, but a roundel with cusps converging from a rim. Hugues Libergier could never have arrived at his solution by merely magnifying a motif already extant; his is a genuine reconciliation of a videtur quod with a sed contra. Note 55

|  |

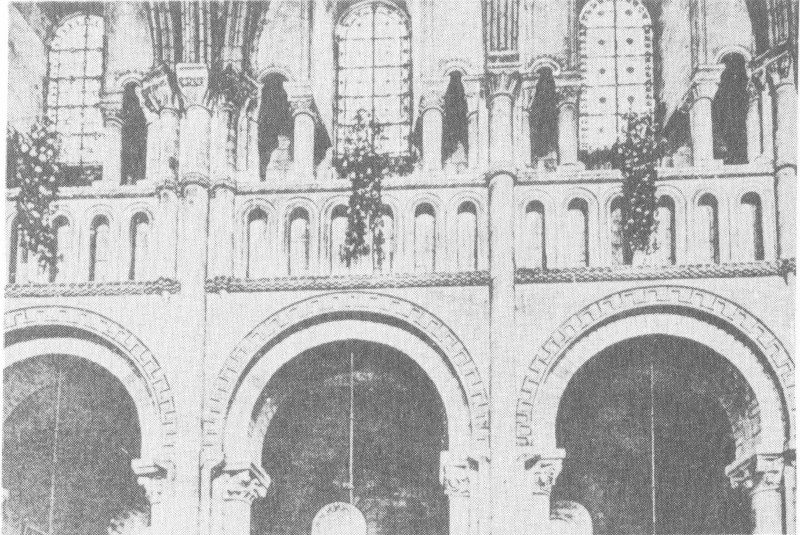

Concerning the problem of organizing the wall beneath the clerestory (unless this wall was eliminated by genuine, independently lighted galleries) the Romanesque style had offered, roughly speaking, two contrasting solutions, one emphasizing the two-dimensional surface and horizontal continuity, the other depth and vertical articulation. On the one hand, the wall could be enlivened by a continuous band of small, evenly spaced wall arches as in Ste.- Trinité in Caen (fig. 37), St.-Martin-de-Boscherville, Le Mans, and the churches of the Cluny-Autun type; on the other, by a sequence of major arches (mostly two to each bay and subdivided by colonnettes so as to constitute dead windows, so to speak) which open onto the roof space above the side aisles as in Mont-St.-Michel, the narthex of Cluny, Sens (fig. 38), etc.

|  |  |  |

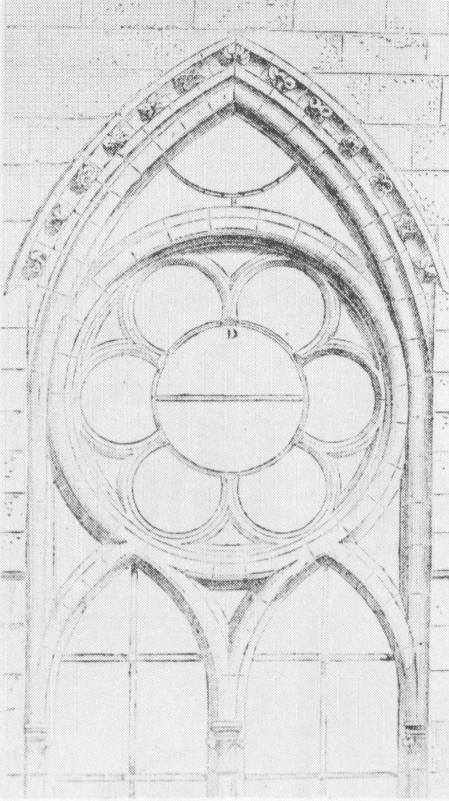

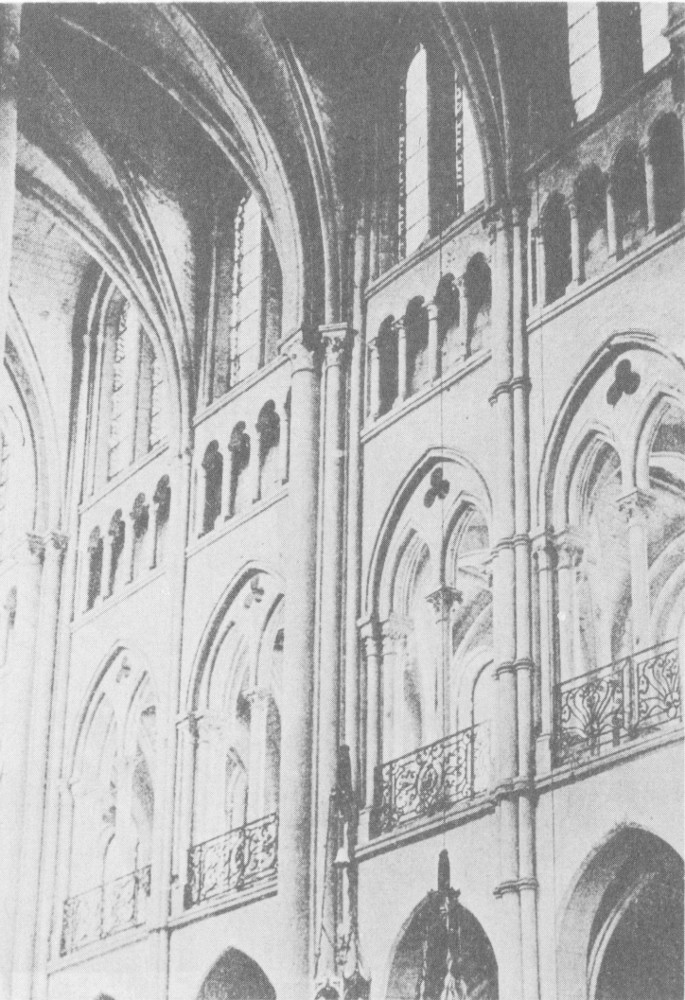

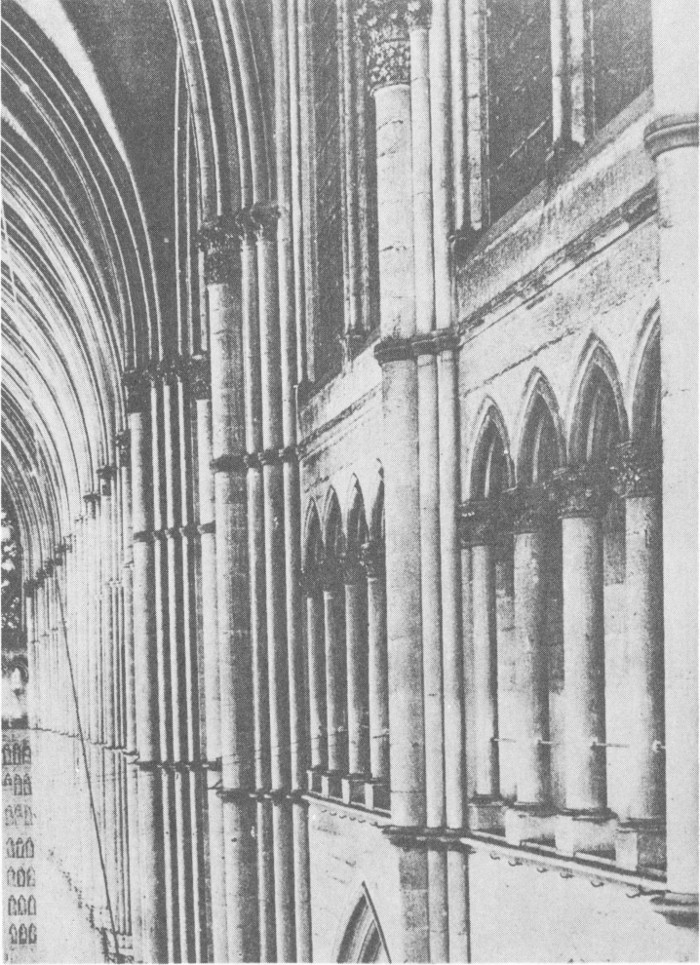

The genuine triforium, introduced in Noyon about 1170 (fig. 39), is a first synthesis of these two types: it combines horizontal continuity with an emphasis on shadowy depth. But vertical articulation within the bay was entirely suppressed, and this was bound to be felt all the more keenly as the clerestory windows had begun to be divided into two lights. Thus in the choir of St.-Remi at Reims and in Notre- Dame-en-Vaux at Châlons-sur-Marne (fig. 40), a shaft or shafts (two in St.-Remi, one in Châlons) were carried from the lower ledge of the triforium right up into the clerestory, where they serve as frames for the windows, trisecting or bisecting the triforium itself. Such a solution was, however, rejected in Laon (fig. 18) as well as, about the turn of the century, in Chartres (fig. 41) and Soissons. In these first High Gothic churches, where galleries were dropped for good and the two lights of the windows were unified into one bipartite plate-tracery window, the triforium still—or, rather, again—consists of perfectly equal interstices separated by perfectly equal colonnettes; horizontal continuity rules supreme, all the more so because the string courses overlap the wall shafts.

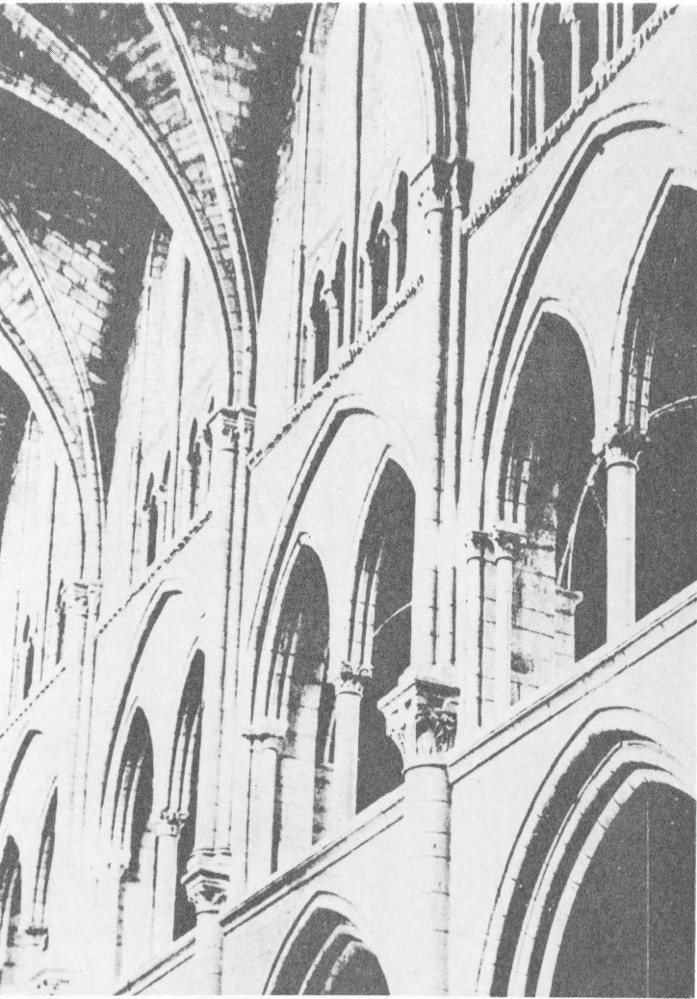

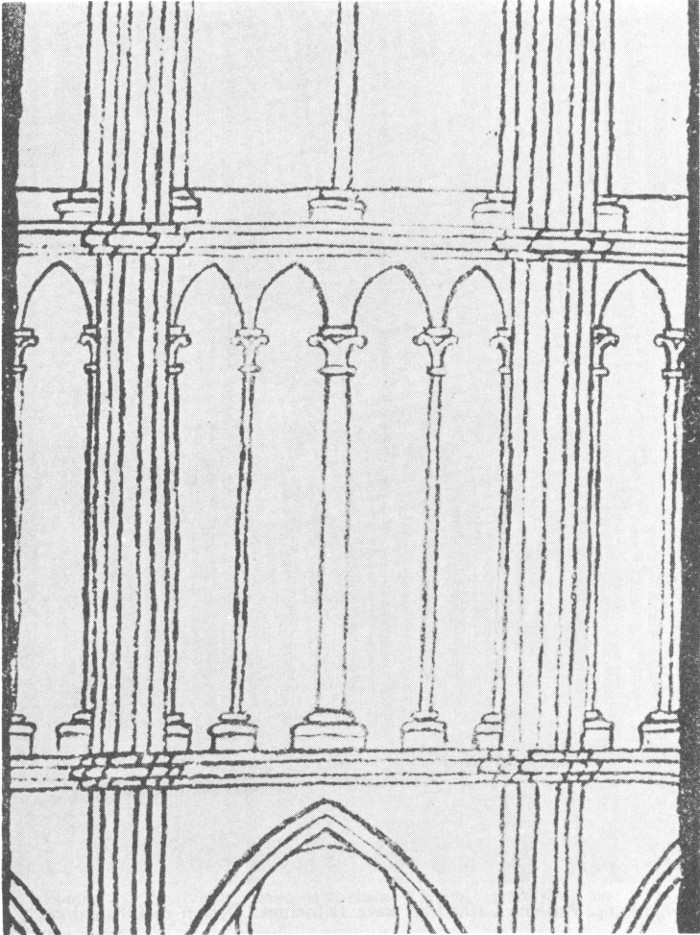

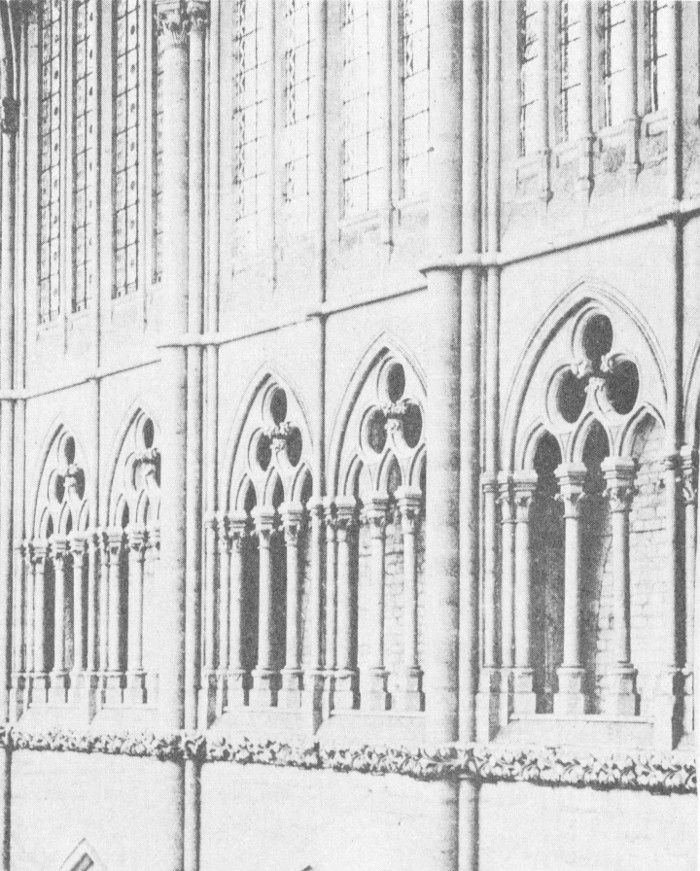

A reaction against this unmitigated horizontalism set in at Reims where the vertical axis of the triforium bays was emphasized by thickening the central colonnettes so that they might correspond to the mullions above them (fig. 42). This was done so discreetly that the modern visitor is likely to overlook it. But the master’s colleagues did perceive the innovation and thought it important: in his sketch of the inner elevation of Reims Cathedral Villard de Honnecourt so enormously exaggerated the slightly stouter proportions of the central colonnette that no one can help noticing it (fig. 43). Note 56 What had been a mere hint in Reims became an explicit and emphatic statement in Amiens (fig. 44). Here the triforium bay was actually bisected, as had been the case in Châlons- sur-Marne and, at an earlier stage of evolution, in Sens: it was cut apart into two separate units, with the central colonnette transformed into a clustered pier the main shaft of which connects with the central mullion of the window.

|  |  |  |

However, in doing this, the masters of Amiens almost negated the whole idea of the triforium, dividing as they did each bay into two “blind windows” and transforming the even sequence of colonnettes into an alternation of members different in kind, viz., colonnettes and clustered piers. As though to counteract this overemphasis on vertical articulation, they accelerated the rhythm of the triforium and made it independent of that of the clerestory. Each of the two “blind windows” that constitute a triforium bay is divided into three sections, whereas each of the two lights that constitute a clerestory window is divided into two. The horizontal element is further stressed by the elaboration of the lower string course into a band of floral ornament.

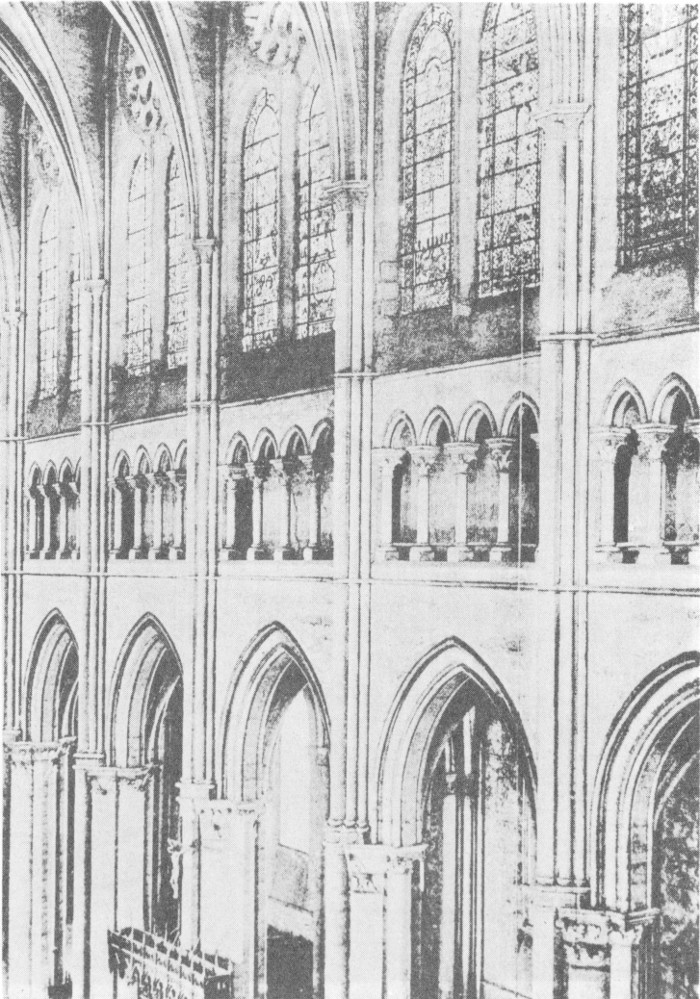

It was left to Pierre de Montereau to say the final respondeo dicendum: as in Soissons and Chartres, the triforium of St.- Denis (fig. 45) is a continuous sequence of four equal openings, separated by members of the same species. However—and this is where Amiens comes in—all of these members are now clustered piers instead of colonnettes, the one in the center somewhat stronger than the others; and all of them are carried up into the quadrupartite window, the central pier by means of three shafts connecting with the primary mullion, the others by means of one shaft connecting with the secondaries. Pierre de Montereau’s triforium is not only the first to be glazed but also the first to effect a perfect reconciliation of the Sic of Chartres and Soissons (or, if you like, Ste.-Trinité-de-Caen and Autun) with the Non of Amiens (or, if you like, Châlons-sur-Marne and Sens). Now, finally, the big wall shafts could be carried over the string courses without fear of disrupting the horizontal continuity of the triforium; and this brings us to the last of our “problems,” the conformation of the nave piers.

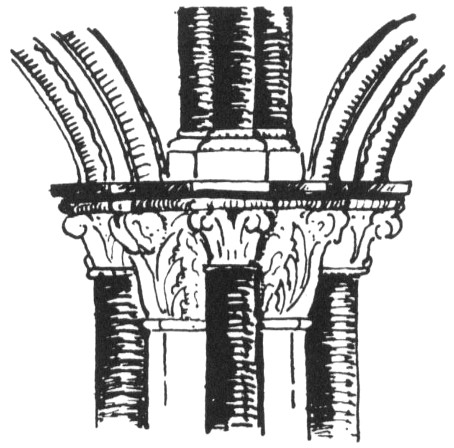

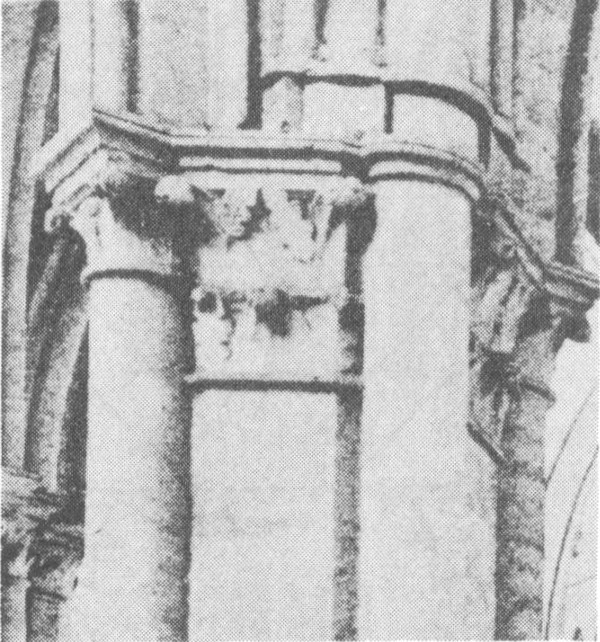

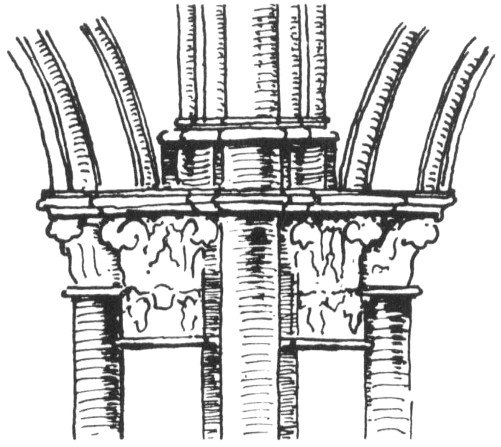

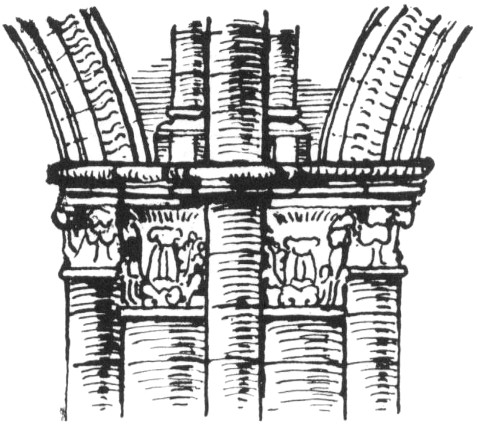

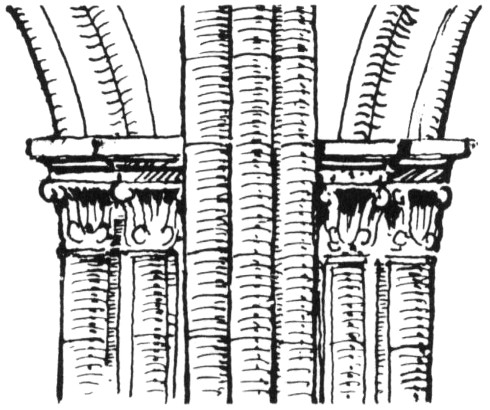

The earliest genuine piliers cantonnés occur, so far as I know, in Chartres Cathedral (begun 1194) where they are, however, not as yet composed of homogeneous elements—a cylindrical core and cylindrical colonnettes—but show, in alternation, a combination of a cylindrical core with octagonal colonnettes and a combination of cylindrical colonnettes with an octagonal core. This latter motif would seem to indicate that the master of Chartres was familiar with a movement, apparently originating in the borderline district between France and the Netherlands, which has left its most important traces in the choir of Canterbury Cathedral. Here William of Sens, magister operis from 1174 to 1178, had almost playfully indulged in inventing all kinds of variations on a modish theme enthusiastically received in England but hardly ever utilized in France—the theme of piers in which a core of light-colored masonry is picturesquely contrasted with completely detached and monolithic shafts fashioned of darkest marble. Note 57 He had produced what may be called a sample card of fancy pier types, and one of these consisted, like the alternate supports at Chartres, of an octagonal core and cylindrical shafts (fig. 46, third pier from left; fig. 54). The master of Chartres adopted this idea but developed it in an altogether different spirit. He retransformed the detached, monolithic shafts into engaged colonnettes constructed of ordinary masonry; he substituted in every second pair of piers a cylindrical core for the octagonal one; and, above all, he employed the pilier cantonné, not as an interesting variant but as the basic element of the whole system. And all the first master of Reims had to do was to eliminate the charming but not quite logical difference in shape between the colonnettes and the core.

In this perfected form, the pilier cantonné is in itself a Sic et Non solution in that it shows colonnettes, originally applied only to angular elements (splayings or piers), in combination with a cylindrical nucleus. But as the early type of triforium tended to suppress vertical articulation in favor of horizontal continuity, so did the early type of pilier cantonné tend to remain columnar rather than “mural.” Like a column, it ended with a capital whereas, in a compound pier, the colonnettes facing the nave were carried through to the springings of the vaults. This created problems which gave rise to a zigzag development similar to that which could be observed in the treatment of the triforium.

|  |  |  |

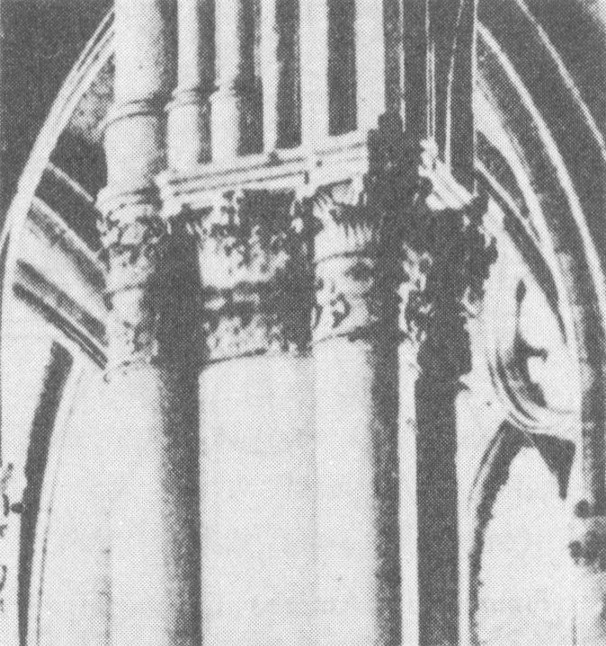

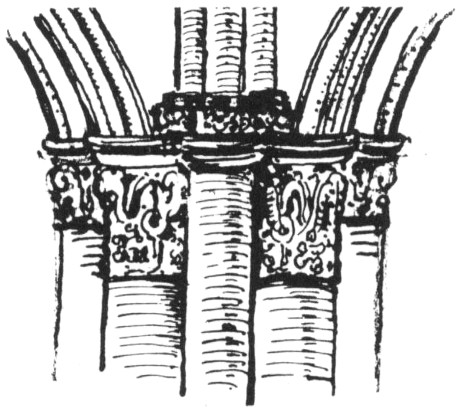

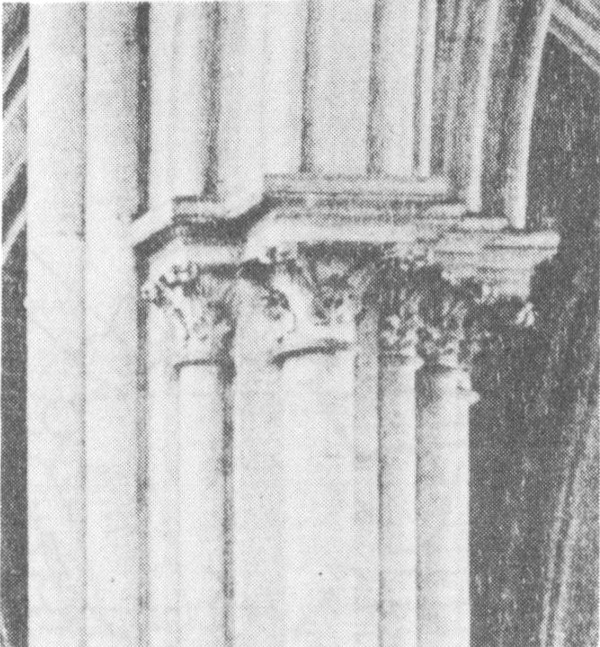

First, since Gothic capitals are proportioned to the diameter rather than to the height of their shafts, Note 58 there came about a combination of one big capital (that of the nucleus) with four small ones (those of the colonnettes) only half as high. Second, and more important, the three—or even five— wall shafts rising into the vaults still started afresh above the capitals as had been the case when the piers were monocylindrical, and it became imperative to establish a visible connection between at least the central wall shaft and what I shall call for short the “nave colonnette,” viz., that colonnette of the pier which faces the nave and not the side aisle or the neighboring pier. The master of Chartres sought to achieve this end by omitting the capital of the “nave colonnette,” which thus continues up to the base of the central wall shaft (fig. 47 and 55). Far from pursuing the same course, the masters of Reims reverted to the earlier form, Note 59 leaving the “nave colonnette” in possession of its capital, and concentrated instead on the other problem, the inequality of the capitals’ heights. They solved it by providing each colonnette with two capitals, one superimposed upon the other, whose combined heights equalled the height of the pier capital (fig. 48 and 56). Note 60

|  |  |

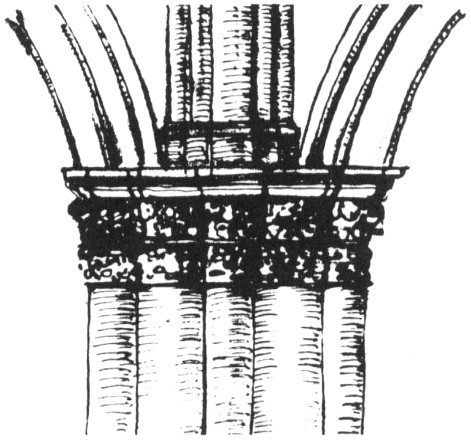

Amiens, on the contrary, reverted to the Chartres type, taking, however, one step farther in the same direction in that not only the capital of the “nave colonnette” but also the base of the central wall shaft was eliminated, so that the “nave colonnette” continues into the central wall shaft itself, not only into its base as in Chartres (fig. 49 and 57). The older piers of Beauvais are generally similar to those of Amiens, but revert to the pre-Amiens tradition in restoring the base to the central wall shaft; and this renewed interruption of vertical coherence is further emphasized by decorative foliage (fig. 58).

|  |  |  to wall and vault-ribs. Design established ca. 1248. |

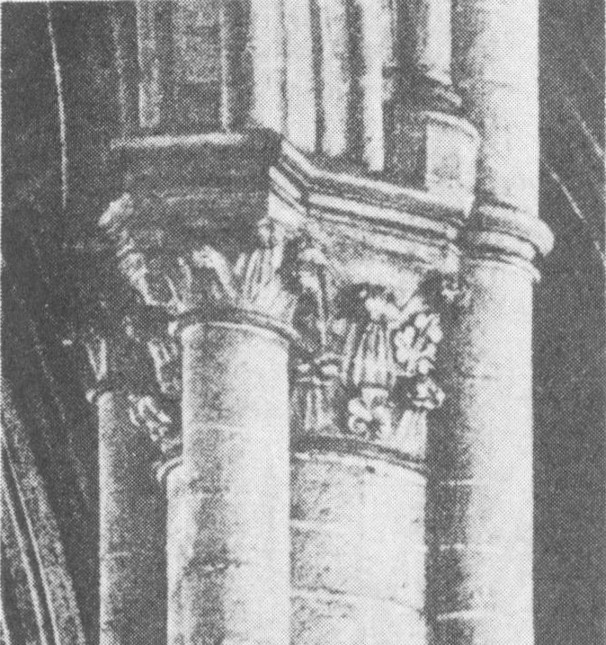

Yet, when the choir of Beauvais was built, the Gordian knot had already been cut by Pierre de Montereau’s bold revival of the compound pier which solved all difficulties in that the big pier capital and the single “nave colonnette” no longer existed (fig. 50 and 59). The three tall shafts required by the main vaults could be run from the floor bases to the springings without interruption, cutting right through the capitals of the nave arcades (fig. 22). However, Pierre de Montereau endorsed the Non rather than reconciled it with the Sic. Wisely subordinating the minor problem of the pier to the major problem of the whole system, he chose to sacrifice the columnar principle rather than to renounce that adequate “representation” of the nave wall by the core of the pier which has been mentioned (fig. 52). In this case, the respondeo dicendum was to be spoken by the French-trained master of Cologne who combined the cylindrical, four-shafted pilier cantonné of Amiens with the tall, continuous shafts and subsidiary colonnettes of Pierre de Montereau’s compound pier. Note 61 But he sacrificed thereby the logical correspondence between the nave wall and the supports. Seen in a diagram, the ground plan of the nave wall again arbitrarily intersects that of the core of the pier instead of coinciding with it (fig. 53).

The gentle reader may feel about all this as Dr. Watson felt about the phylogenetic theories of Sherlock Holmes: “It is surely rather fanciful.” And he may object that the development here sketched amounts to nothing but a natural evolution after the Hegelian scheme of “thesis, antithesis, and synthesis”—a scheme that might fit other processes (for instance, the development of Quattrocento painting in Florence or even that of individual artists) just as well as it does the progress from Early to High Gothic in the heart of France. However, what distinguishes the development of French Gothic architecture from comparable phenomena is, first, its extraordinary consistency; second, the fact that the principle, videtur quad, sed contra, respondeo dicendum, seems to have been applied with perfect consciousness.

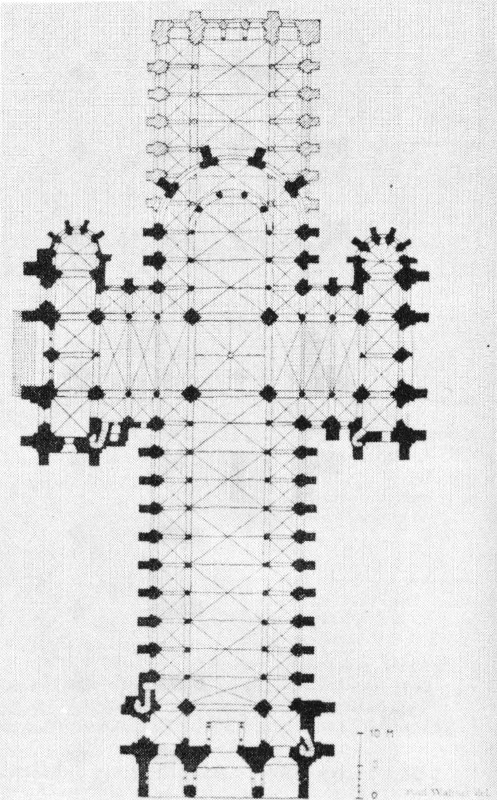

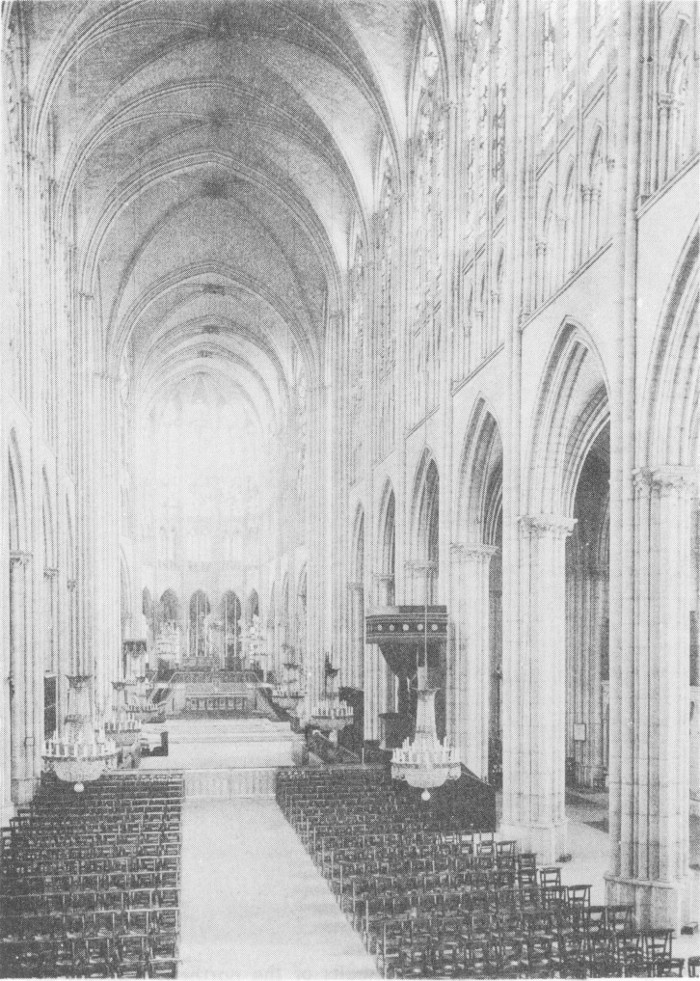

There is one scrap of evidence—well known, to be sure, but not as yet considered in this particular light—which shows that at least some of the French thirteenth-century architects did think and act in strictly Scholastic terms. In Villard de Honnecourt’s “Album” there is to be found the groundplan of an “ideal” chevet which he and another master, Pierre de Corbie, had devised, according to the slightly later inscription, inter se disputando (fig. 60). Note 62 Here, then, we have two High Gothic architects discussing a quaestio, and a third one referring to this discussion by the specifically Scholastic term disputare instead of colloqui, deliberare, or the like. And what is the result of this disputatio? A chevet which combines, as it were, all possible Sics with all possible Nons. It has a double ambulatory combined with a continuous hemicycle of fully developed chapels, all nearly equal in depth. The groundplan of these chapels is alternately semicircular and—Cistercian fashion—square. And while the square chapels are vaulted separately, as was the usual thing, the semicircular ones are vaulted under one keystone with the adjacent sectors of the outer ambulatory as in Soissons and its derivatives. Note 63 Here Scholastic dialectics has driven architectural thinking to a point where it almost ceased to be architectural.