Wyndham Lewis’ The Apes of God

Source#

Source#

From The Jonathan Bowden Archive

Wyndham Lewis’ The Apes of God#

The Apes of God happens to be one of the most devastating satires to be published in the English language since the days of Dryden and Pope. It appeared in a Private Press edition (prior to general release), and at over 600 pages it was the size of your average London telephone directory.

The Apes deals, in ultra-modernist vein, with a catalog or slide-show of dilettantes from the London of the inter-war period. It is, in reality, a gargantuan satire against the Bloomsbury Group and all of its works. The historical importance of the Bloomsbury Group is that they were the incubator for all the left-liberal ideas which have now hardened to a totalitarian permafrost in Western life. This is the real and crucial point of this gargantuan effort — an otherwise neglected work.

To recapitulate some of the detail: the novel concerns the sentimental education of a young idiot (Dan Boleyn) in the ways of Bloomsbury (apedom). During this prologue he meets a great galaxy of the millionaire bohemia so excoriated by Lewis. The chapters and sub-headings basically deal with his education in ideological matters (not that the simpleton Dan would see it in that way), and he is assisted in his insights by Pierpoint (a Lewis substitute), the Pierpointian ventriloquist and contriver of ‘broadcasts’, Horace Zagreus, as well as Starr-Smith. The latter is Pierpoint’s political secretary, a Welsh firebrand, who dresses as a Blackshirt for Lord Osmund’s fancy-dress or Lenten party which makes up a quarter to a third of the book.

The liberals who are dissected are James Julius Rattner (a Semitic version of James Joyce), Lionel Kien and family, Proustians extraordinaire, various poseurs and Bullish lesbians, as well as the Sitwell family group who are depicted as the Finnian Shaws. The Sitwells are all but forgotten today, but they were highly influential in the world between the Wars — as is witnessed in John Pearson’s masterly biography Facades: Osbert, Edith and Sachaverell Sitwell. It is no accident to say that this satire has kept the Sitwells in contemporary culture, despite the fact that they are the butt of Lewis’ ferocious wit.

Throughout this odyssey through Apedom various themes are disentangled. The first is a penchant for the class war — in a parlor Bolshevik manner — from those who superficially have the most to lose from it. This leads to an active collaboration between masters and servants ahead of time. The next “war” to which these pacifists hook their star is the age-war between the generations which is best illustrated by the Sitwells’ attitude to their aged Patriarch, Cockeye in the novel.

Other cults or pseudo-cults of the lower thirties (i.e., the twenties) were the cult of the child, feminism of various kinds, the glorification of the negro (witness the work of Firbank, for instance), and the ever-present cult of homosexuality. As Horace Zagreus — one of Lewis’ voices in the novel — acidly points out: as far as Bloomsbury was concerned, heterosexuality was the love that dare not speak its name.

All of these putative forms of political correctness were held together by a rising generation whose most ‘advanced’ adherents were determined to let their hair down during the roaring ’20s. Indeed, the cloying, ormolu tainted facade of the super-rich — anatomized in this novel — only came to an end with the Great Crash, which burst at about the time of the novel’s appearance in 1930.

The semantics of the radical bourgeoisie have largely taken over the world — and what was anathema to mass or philistine opinion is now the normal chit-chat of the semi-educated to educated. Revolutionary bohemia — according to Lewis — proceeds in three stages. First you have the aristocratic version of it during the 1890s — the “naughty nineties,” the breaking of Oscar Wilde, etc., only for this stage to be followed by a mass bourgeois version of la Decadence in the 1920s. This makes way for the mass proletarianized version of bohemia which hits the world in the 1960s, after a few beatnik preliminaries the decade before. Lewis never lived to see this period, having died in 1957.

Another very interesting feature about Lewis’ prescience is his understanding of revolutionary ideology and its after-effects. For, as early as The Art of Being Ruled in 1926, Lewis was positing the notion that the emancipation of women to work would kill off the family far more effectively than all the feminist route-marches put together.

One of Lewis’ most extraordinary judgments is that many Marxian values, floating freely and slip-streaming their historical source, could make use of market capitalism to achieve their ends. This was an insight of such penetration and Chestertonian paradox in 1926 that it must have appeared half-insane.

Other ancillary positions which were part of this Super-structuralist ramp (sic) were the cult of the exotic and the Primitive in art, Child art and children’s rights, Psycho-analysis, and hostility to all prior forms.

The revolutionary thinker Bill Hopkins once said to me that one of the reasons for the obsession with primitivism in early modernism was a reaction to Western thought’s compartmentalization in the late nineteenth century. This led to a desire to kick against the pricks and develop contrary strategies of pure energy in the Arts. Whatever the truth about this, a hostility towards the martial past, nationalism, imperialism, race and empire — the entire rejection of Kipling’s Britain — was part-and-parcel of the Bloomsbury sensibility.

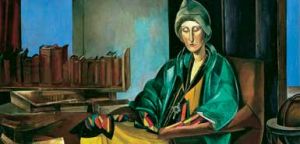

Nonetheless, it goes without saying that Lewis, the founder of the Vorticist movement inside modernism, saw modern art as a weapon in his battle against The Apes of God. In this regard Lewis was that very rare animal — a thoroughgoing modernist and a right-wing transvaluator of all values.

Interestingly, the idea of The Apes comes from the dilettantist perquisite of thousands of amateur painters, poets, sculptors, writers and the rest, themselves all part of a monied bohemia, who crowd out the available space for genuine creatives like himself. The cult of the amateur, however, would soon be replaced by the general melange of entertainment and the cultural industry which has probably stymied a great deal of post-war creation that Lewis never lived to see.